O, say can you see: The not-so-well-known history behind our nation’s anthem

Ask folks where our national anthem got its start, and most are quick to point at a man named Francis Scott Key, a lawyer by trade.

Not just any ol’ lawyer, either. He became the federal prosecutor for Washington, D.C., a prestigious post, indeed. Came complete with a Presidential nomination and everything. That Andrew Jackson was a longtime friend mattered little because he’d earned his chops the old-fashioned way, case by case.He was good, too. Quite the grizzly in the courtroom, by all accounts. He built a reputation for not only accepting some of the toughest cases around but usually landing the most favorable outcomes for his clients.

Still, no matter how impressive he might be in an argument, Key wouldn’t be most folks first choice as songwriter. Not for something as grand in scale as a nation’s anthem, anyway. Apart from legal briefs, he wasn’t a writer of any real merit. He might’ve dallied some with verse, but poet laureate he was not. Nor was he a composer of grand musical scores.

He was just a lawyer.

But what if I told you that the very same song – the one we now all rise for, remove our hats, and pause whatever we’re doing right then to offer our salute, either actual military-styled or with palms pressed to our hearts – was actually written as a drinking song, of sorts, complete with lyrics so loaded in inuendo and bawdy humor that it literally ended the group it was written for?

Because that’s all true, too.

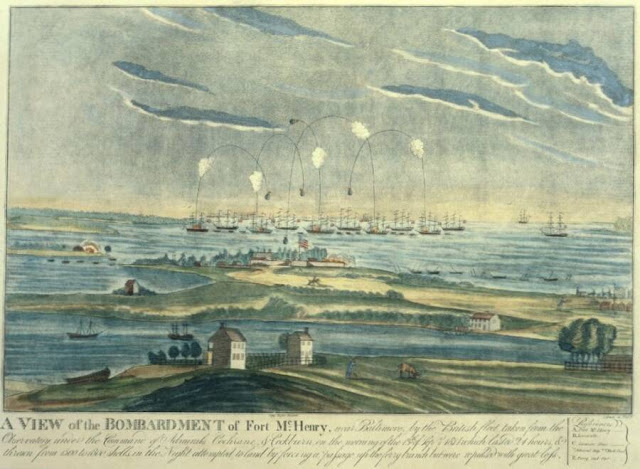

So it was, however, that on Sept. 14, 1814 — precisely 208 years ago last Wednesday — a Maryland attorney found himself alongside one Col. John Skinner boarding His Majesty’s Ship, the Tonnant, at the personal invite of British Vice Adm. Alexander Cochrane, British Rear Adm. George Cockburn and British Maj. Gen. Robert Ross, just moments before the Battle for Baltimore would begin.

Key didn’t know it yet, but touching his foot to the planks of that deck would forever change his life. It set into motion a whole series of events no one might’ve predicted, all of which placed him in perhaps the most perfect place at just the right time.

For there he would witness the kind of events that were shocking by their sheer enormity and spectacle. Some might even call them appalling, and in the same moment, terrifying, as well. But what a sight it must’ve been. It was the kind of thing that can forever change a man, and it began with a single step.

***

As a lawyer, Key built quite the name for himself. It began in 1807, defending Justus Eric Bollman and Samuel Swartwout who had been charged with treason in connection to an alleged conspiracy designed by Aaron Burr. Key also served as a personal advisor to Andrew Jackson and with his help, he was later appointed the District Attorney for the District of Columbia from 1833 to 1841.

In that final capacity, he took on several high-profile cases. Like assisting in the prosecution of Tobias Watkins, who worked with the U.S. Treasury under President John Quincy Adams, for misappropriating public funds of all things. He prosecuted Richard Lawrence, an introverted house painter who lived in nation’s capital, for his attempt to assassinate President Andrew Jackson at the top steps of the Capitol, as the president was exiting a funeral service held there.

Lawrence walked up to Jackson through a crowd, drew his pistol, carefully aimed it, and fired — twice, repeating the process all over again with yet another pistol — both of which ended in misfires.

Lawrence walked up to Jackson through a crowd, drew his pistol, carefully aimed it, and fired — twice, repeating the process all over again with yet another pistol — both of which ended in misfires. Jackson wasn’t letting him try again, however. He took to walloping the man with his cane until members of public intervened. Davy Crocket, of all people, was attending the same funeral, saw what was happening and wrestled the would-be assassin to the ground until police arrived.

It was the first attempt, ever, to kill a seated American president, and by Jackson’s reckoning, it should’ve been an open and shut case. It wasn’t, mostly because it was obvious that Lawrence didn’t have a speck of sanity left in him. Took the jury about five minutes to render not guilty verdict, though Key did make sure Lawrence never saw so much as a tincture of freedom. Still, Jackson would’ve much preferred seeing him hanged.

Although proven in multiple eras now that Lawrence was indeed a lunatic who acted alone, Jackson went to his grave swearing his political adversaries had sent Lawrence to end him.

Incidentally, those guns of Lawrence’s, the two that misfired: On every subsequent test fire of both weapons for years afterward they fired true and instant, every time they tried. That both misfired, on THAT day, was nothing short of miraculous.

***

Far and away Key’s most famous client was easily Texas’ own Sam Houston, who, years before Jackson would wail on his would-be assassin, made his own headlines by taking up his cane against one Rep. William Stanbery of Ohio. Fed up with the repeated character attacks lobbed at him by Stanbery, Houston tore into him one day when, when entirely by chance, the two crossed paths on the street on the street one day as Houston was walking to the theater with a couple of his senator friends.

That Stanbery had just given a speech from the House floor a couple days prior calling Houston a crook and a fraud certainly didn’t matters any, nor did his ignoring Houston’s demands for an apology. Between wallops, the much smaller Stanbery finally managed to pull out one of the two pistols he carried, which he then cocked and fired point blank into Houston’s heart.

That Stanbery had just given a speech from the House floor a couple days prior calling Houston a crook and a fraud certainly didn’t matters any, nor did his ignoring Houston’s demands for an apology. Between wallops, the much smaller Stanbery finally managed to pull out one of the two pistols he carried, which he then cocked and fired point blank into Houston’s heart. And just like with Jackson, nothing happened.

Well, almost nothing. Sure, the pistol misfired, but Houston came completely unhinged when he saw the congressman had to tried to shoot him. Houston didn’t stop whacking on the old boy until he’d plum worn himself out. Then, he spent a few moments catching his breath, straightened himself up, and continued on to the theater as if nothing had happened, leaving Stanbery to lie there in his own urine and bleed.

Ol’ boy had it coming, in Houston's mind. He deserved what he got. Besides, this was HIS town, by God. Houston knew full well how that place worked.

Thing is, though, folks who whup up on an elected official on a public street in broad daylight and then stroll off to laugh it up with their senator buddies at the theater, tend to set people on edge, especially the type of people who hang around the nation’s capital. So, when his federal arrest warrant got served, Houston was probably the only one surprised by that fact in all of Washington, D.C.

He was going to need a big gun on this, which was how he came to Key, the anthem writing attorney.

***

Key was brought in to work his magic and make Houston’s charges disappear. Probably would have, too. If only he could get Houston to shut his trap for half a moment.

That Houston didn’t kill Stanbery that day with his cane was a sheer miracle. Houston would later attribute that fact to Stanbery having a head as hard as a full sack of hammers. In court, no less. Much to the amusement of everyone there that day.

Everyone, that is, but the judge. Calling for order, that judge must’ve banged his gavel enough times to build a whole house full of furniture. And, of course, he already warned Houston against his smart-alec responses. His was a court of law, not a performance stage to try out his material. Mistake the two once more, the judge warned him, and Houston would be held in contempt.

All this happened BEFORE Houston ever set foot in Texas. Immediately before, in fact. Some have even argued that his departure came BECAUSE OF all the unpleasantness that trial dredged up. It damaged him politically, that much was certain. It marred his reputation and created a chink in his armor that rivals would forever thereafter aim for. And he knew it, some have argued. Only by getting away and letting the dust settle a while would the smell of blood ever dissipate in the shark pit otherwise known as Washington, D.C.

Some men, however, never could sit idly by.

Though the quote is attributed to Davy Crockett, some months later, following a particularly stinging political defeat, it isn’t hard to imagine Houston having said something similar as he rode out of town into the setting sun, bound for Nacogdoches.

“Y’all can all go to Hell,” he’d shout over his shoulder, never once looking back. “I’m going to Texas.”

It wouldn’t be hard to imagine Crocket, there to watch as Houston rode away, stepping out from the shadows and lighting a cigar, shaking his head and smiling as he repeated the phrase, “…I’m going to Texas. I’ll have to remember that one. That’s some good stuff, right there.”

Still, Houston could’ve been rotting away in a prison cell someplace, were it not for Key. He was facing some serious charges by those who didn’t care the least bit for him.

Where would we be today if Houston hadn't bought the Texans some time before they finally stood their ground at San Jacinto, and after months of fighting and countless lives were lost, Houston and his men ended the whole sorry mess in just minutes. It was a victory that secured Houston an easy presidency in the new Texas republic, and later, yet another state governorship, and later still, yet another congressional seat, too. He’s the only man, ever, to be elected governor and congressman in two separate states.

And he’s got Key to thank for most of it.

Key wasn’t making social calls the day he and Col. Skinner boarded the HMS Tonnant. He was all business, in fact. There to handle some legal matters and be on his way, which no doubt made the Navy men’s pleasantries and invitation to join them for dinner as odd as it was irritating.

These were same British troops who sacked the nation’s capital that very week. They even torched the White House. That very day. It was burning still as Key left Washington, D.C. He could easily have seen the columns of black smoke rising still from there on the boat, it’s certain.

Plus, the Brits had also taken prisoners, one of Key’s friends among them, a doctor from Prince George’s County in Maryland. It was why Key was there from the start. Skinner needed a negotiator, and Key was one of the best. While they dined, considering the American proposal, they made light conversation and were even cracking jokes, the 35-year-old would later note in a memoir he penned, not long before his own death at the age of 63.

Key and company, which now included both Skinner and Dr. William Beanes, the prominent Upper Marlboro physician, who showed up drunk, rambling about some eminent seaboard attack.

It was how he got captured, they figured, not what was about to happen. On that, they still knew nothing.

Until they parted ways. Healthy handshakes all around, he, Skinner and Beanes made their departure as the day’s sun was already near gone. When the vice admiral suggested they take along a small detachment to act as escort, it seemed genuine enough. No point spoiling good food and good liquor rowing half the Chesapeake in the dark. Let the youngsters tend to the oars, he urged.

Who could argue such fine logic?

Wasn’t until they got back to their own boat that their real purpose became evident. Their orders were to hold them there until the attack had ended, all under the guise of concern for their safety, of course. The truth of the matter was that they were now prisoners aboard their own vessel, captives of the very same detachment they’d misinterpreted as a kindness until just then.

That’s when the shelling started. An endless array, all aimed at the place both Key and the good doctor called their home. That was their neighbors, their friends and their families at the receiving end of those bombs.

And all they could do was watch.

For 25 long hours, no less, never ceasing until near sunup the next day. Probably ran out of stuff to shoot at them, Key probably thought. Of course, it may be over, too. The Brits had won and the fort at Baltimore had fallen. They wouldn’t know for sure until more of the sun found its way into the sky.

And he’s got Key to thank for most of it.

***

Key wasn’t making social calls the day he and Col. Skinner boarded the HMS Tonnant. He was all business, in fact. There to handle some legal matters and be on his way, which no doubt made the Navy men’s pleasantries and invitation to join them for dinner as odd as it was irritating.

These were same British troops who sacked the nation’s capital that very week. They even torched the White House. That very day. It was burning still as Key left Washington, D.C. He could easily have seen the columns of black smoke rising still from there on the boat, it’s certain.

Plus, the Brits had also taken prisoners, one of Key’s friends among them, a doctor from Prince George’s County in Maryland. It was why Key was there from the start. Skinner needed a negotiator, and Key was one of the best. While they dined, considering the American proposal, they made light conversation and were even cracking jokes, the 35-year-old would later note in a memoir he penned, not long before his own death at the age of 63.

Key and company, which now included both Skinner and Dr. William Beanes, the prominent Upper Marlboro physician, who showed up drunk, rambling about some eminent seaboard attack.

It was how he got captured, they figured, not what was about to happen. On that, they still knew nothing.

Until they parted ways. Healthy handshakes all around, he, Skinner and Beanes made their departure as the day’s sun was already near gone. When the vice admiral suggested they take along a small detachment to act as escort, it seemed genuine enough. No point spoiling good food and good liquor rowing half the Chesapeake in the dark. Let the youngsters tend to the oars, he urged.

Who could argue such fine logic?

Wasn’t until they got back to their own boat that their real purpose became evident. Their orders were to hold them there until the attack had ended, all under the guise of concern for their safety, of course. The truth of the matter was that they were now prisoners aboard their own vessel, captives of the very same detachment they’d misinterpreted as a kindness until just then.

That’s when the shelling started. An endless array, all aimed at the place both Key and the good doctor called their home. That was their neighbors, their friends and their families at the receiving end of those bombs.

And all they could do was watch.

For 25 long hours, no less, never ceasing until near sunup the next day. Probably ran out of stuff to shoot at them, Key probably thought. Of course, it may be over, too. The Brits had won and the fort at Baltimore had fallen. They wouldn’t know for sure until more of the sun found its way into the sky.

***

If you’re looking for the man to thank—or blame, as the case may be—for the sheet music to our national anthem, you’re probably gonna need a boat. And I’d probably bring a shovel, too…

If you’re looking for the man to thank—or blame, as the case may be—for the sheet music to our national anthem, you’re probably gonna need a boat. And I’d probably bring a shovel, too… Because Londoner John Stafford Smith, was a British composer, church organist and choir leader, as well as an early collector of oddities and antiquities. He had handsome collection of hand scripted sheet music by Johann Sebastian Bach, but that was like 250 years ago.

Even if you sailed really fast, I doubt you’ll catch him. Unless, of course, you top 88 mph and travel back in time (that’s a Back to the Future movie reference, for you youngsters out there). And as to the shovel: Just in case that boat of yours DOESN’T have a flux capacitor. . .

I will warn you, though: If you’re looking for someone to swap stories with about patriotism and national pride, you can probably save yourself a trip. Based on the version of that song published in London’s The Vocal magazine, just two years after we became a country, in 1778, I’m pretty sure you’re barking up the wrong tree anyway, if that’s your intent.

Our nation’s anthem was right about the last thing its writer had in mind with this piece.

Smith would call his tune “To Anacreon in Heaven,” which, incidentally, were the first four words to the lyrics that a man named Ralph Tomlinson, another fine lawyer, wrote to accompany Smith’s melody. Tomlinson is listed as president of the Anacreontic Society, a group that made the words of his song their official “constitutional song.”

For those not familiar with a constitutional song, it has nothing to do with our nation’s founding document. Rather, it’s a type of song that serves as a rally cry for its members, allowing one to quickly ascertain the number of brethren he might have in an audience, as those familiar with it will typically join in. Think something along the lines of the songs associated with our military branches. Or, a university’s alma mater or fight song, perhaps. Plus, just as those songs do, they tell you something about the group as well.

So, what’s this Anacreontic Society?

By all accounts this group made music its pivotal focus, as many core members worked within the profession themselves in some compacity. In the roughly decade-and-a-half they are said to have conferred regularly, they played host some the finest musicians, singers and composers who ever lived, people like Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Antonio Salieri, Johan Sebastian Bach, and Ludwig Van Beethoven, to name but a few.

But the Anacreontic Society was also one of several private gentlemen’s clubs that rose in popularity across Europe at the time, in every way the label might imply. The root of word Anacreontic is Anacreon, who was a Greek poet from the 6th Century B.C., best known for his ditties about women, wine and indulging in good times.

So, that’s why Smith wrote “To Anacreon in Heaven,” so club members would have a song to sing when they really kicked off the evening’s entertainment.

Most of their gatherings had a main guest performer, after which they’d begin serving their evening’s feast and libations. Those involved elaborate multicourse meals, usually, with liquors from every corner of the globe. Once everyone started to limber up and try some of the more exotic menu items, some would usually fire up the constitutional song—intentionally written so it’s difficult to sing, with leaps of more than an octave. Because most in this circle were true musical elitists, who loved nothing more than showing off, or failing that, at least being able to tell you that you’ve done it all wrong.

Moving through its lyrics, the song just gets bluer the farther one gets in the song. The language is of 18th Century propriety, of course. Yet they’re loaded with double entendre and contain all the subtlety of a dirty limerick. It doesn’t take a literary genius to realize that a phrase like “entwine the myrtle of Venus with Bacchus’s vine” isn’t always referring to flowers and grapes in every reference.

***

Keep in mind, these aren’t your average blue-collar stiffs, forced to toil for their livings. In fact, few had ever seen a hard day's labor their whole lives. They were men of privilege. Most were direct descendants of England’s oldest and most powerful families. They were the ruling class, whose grandfather’s grandfathers, perhaps, were pursed title and lands in exchange for their loyalty and the strength of those at their command.

Albeit most are little more than distant cousins to the true-blue seated aristocracy, far enough removed they’d never warrant a title. Still, most grew up in the shadows of palaces. They may be illegitimate sons of a palace chamber maid, but they grew up playing with princes and future dukes.

As such, most were well-educated, well-bred, well-dressed and well-financed individuals. Or at least pretending to be in order to run in such circles. And they were always looking to out-do one another. Extravagance was key to clubs like these, and they became quite famous for their many indulgences and debaucheries of every sort, especially as the night wore on. They were the types of people who hosted the types of parties that England’s Romantic poets would try and crash every night—men like John Keats, Percy Shelley and Lord Byron—drunks, hedonists and philanderers, every last one.

And if you ran with crowds like those, you valued just one other quality, something you’d seek out in all prospective club members.

That is, drag-it-with-you-to-the-grave discretion. After all, many held positions of prestige and influence. Several had wives and families waiting for them back home. So, they demanded certain facts about themselves and their behavior, especially at the end of a long night’s drink, remain among friends.

What happens at Anacreontic Society, stays at Anacreontic Society, they’d pretty well insist.

Such sworn secrecies are never free, of course, and while most tended to frown on outright extortion, even back then, there were plenty of other currencies to be bartered with in a roomful of London’s richest and most powerful men. Favors were held in highest esteem, be it forgiving a debt, perhaps, or simply an introduction made in a society that still pandered to such airs. All so the menfolk who behaved like drunken wild apes after dark could still stroll about with their little ones and wives in the daytime, their secrets safely stowed at whatever gentlemen’s clubs they frequented.

And from such lowly and carnal debaucheries sprang our nation’s anthem, straight from the gutters of London. It’s why melody even exits. It’s a song about exploring indulgences of every sort and satisfying whatever appetites those indulgences may stir.

For those who might doubt such an estimate, consider this: The Anacreontic Society came to an end after the Duchess of Devonshire attended one of its meetings. Because “some of the comic songs [were not] exactly calculated for the entertainment of ladies, the singers were restrained; which displeasing many of the members, they resigned one after another; and a general meeting being called, the society was dissolved,” according to the memoirs of one William Thomas Parke, a musician and dues-paying member.

For those who might doubt such an estimate, consider this: The Anacreontic Society came to an end after the Duchess of Devonshire attended one of its meetings. Because “some of the comic songs [were not] exactly calculated for the entertainment of ladies, the singers were restrained; which displeasing many of the members, they resigned one after another; and a general meeting being called, the society was dissolved,” according to the memoirs of one William Thomas Parke, a musician and dues-paying member. It's not clear exactly when this incident occurred, but in October 1792 it was reported that “The Anacreontic Society meets no more,” as it had long been struggling with symptoms of internal decay, Parke went on to say.

Though the monthly gentlemen’s club meetings may have ceased, Smith’s unique tune no doubt lived on, eventually finding its way from the pubs and taverns of London to those found in the colonies of the new world. Sure, they may have been founded a bunch of religious zealots, but taverns and pubs still did quite well on this side of the Atlantic, and men like Samuel Adams made a fortune because of it.

***

Anxious to see how much of his hometown of Baltimore was still standing, Key climbed up on his ship’s railing come first light and gazed across the steaming waters. As the mist slowly cleared, there she was, as surprising as she was inspirational: A star-spangled banner still fluttering proud.

Key fully expected to be greeted by the Union Jack that day, he'd later write, indicating that the Brits now held the seaside fort. It’s why the English had been so painstaking in their bombardment, no doubt.

Seeing Old Glory instead, Key never felt more inspired.

He needed a pen. Once in hand, he patted his coat pockets for ink. And what’s that? Ah! An envelope. That’ll do. He inks up and gets scribbling. The words flowed faster than he could get them down. Words like “rocket’s red glare” and “bombs bursting in air,” and how despite all that, they still “gave proof through the night that their flag was still there.”

This thing practically wrote itself.

Say, the wind seems to be picking up, because look at it, just fluttering there in the breeze.

Sneeze and sleaze rhyme with breeze…

But what if? YES! That’s perfect: “O say, does that star-spangled banner yet wave…” which sets up perfectly for that “home of the brave” bit. He wasn’t exactly sure where that came from, but he awoke with that one on his lips that morning. And considering he’d already tapped the Anacreontic Song for another tune he’d put together just a couple years prior, why not tap it again.

That home of the brave part sure had a nice ring to it, he thought. He’d put it to use for sure now.

So it was that Francis Scott key penned his tribute to America, a work begun there on the ship he overnighted in on the bay. He completed the poem at the Indian Queen Hotel, where he stayed a couple nights more to finish his manuscript, which he left untitled and unsigned.

When printed as a broadside, it was given the title “Defence of Fort M'Henry.” It was first published nationally in The Analectic Magazine after Washington Irving, then editor of the Analectic, heard it performed one night at local tavern.

Key was inspired by the enormous 20-foot by 30-foot U.S. flag, with 15 stars and 15 stripes, that would forever thereafter be called the Star-Spangled Banner.

Sneeze and sleaze rhyme with breeze…

But what if? YES! That’s perfect: “O say, does that star-spangled banner yet wave…” which sets up perfectly for that “home of the brave” bit. He wasn’t exactly sure where that came from, but he awoke with that one on his lips that morning. And considering he’d already tapped the Anacreontic Song for another tune he’d put together just a couple years prior, why not tap it again.

That home of the brave part sure had a nice ring to it, he thought. He’d put it to use for sure now.

***

So it was that Francis Scott key penned his tribute to America, a work begun there on the ship he overnighted in on the bay. He completed the poem at the Indian Queen Hotel, where he stayed a couple nights more to finish his manuscript, which he left untitled and unsigned.

When printed as a broadside, it was given the title “Defence of Fort M'Henry.” It was first published nationally in The Analectic Magazine after Washington Irving, then editor of the Analectic, heard it performed one night at local tavern.

Key was inspired by the enormous 20-foot by 30-foot U.S. flag, with 15 stars and 15 stripes, that would forever thereafter be called the Star-Spangled Banner.

Much of the idea of the poem, including the flag imagery and some of the wording, is derived from an earlier song by Key, also set to the tune of “The Anacreontic Song.” It was known as “When the Warrior Returns,” was written to honor Stephen Decatur and Charles Stewart on their recent return from the First Barbary War.

Immediately popular, it was later renamed the Star-Spangled Banner, and it got performed frequently at various pubs and venues. The Civil War brought the song to even greater national prominence, its lyrics deeply meaningful to Union troops at a time when the American flag was under attack by Confederate forces.

Congress did not designate the song as our national anthem until 1931, overcoming years of opposition from those who disliked the song, including prohibitionists and some religious leaders who seized on the tune’s origins to label it “a barroom ballad composed by a foreigner.”

Critics have never stopped seeking a new anthem, often using the same complaints.

“Our National Anthem is about as patriotic as 'The Stein Song,' as singable as Die Walkure, and as American as ‘God Save the Queen,’ ” one wrote in 1965.

The song “bristles with a blood-and-thunder spirit we neither feel nor want,” a Washington Post music critic wrote in 1977.

That Francis Scott Key, a lawyer, would author our nation’s anthem remains a bit of an oddity to me.

It may not have been so odd coming from that other famous Francis Scott, a distant cousin of Key’s who dropped the girly first name and preferred just a letter instead. They’d call him F. Scott Fitzgerald, author of four novels and 164 short stories, and some say, one of the greatest writers ever in America. If he had written the national anthem, it would have elevated its merits some, perhaps, made it the official song of our country just that much sooner.

Of course, his version would’ve probably sounded more Jimi Hendrix’s version. He was all about the jazz era, after all.

But a lawyer?

Not everyone hated it, of course. “The Star-Spangled Banner” was loved by American composer and bandleader John Philip Sousa. He considered it a “soul-stirring song,” and once offered following about it: “Nations will seldom obtain good national anthems by offering prizes for them,” he said. “The man and the occasion must meet.”

Not everyone hated it, of course. “The Star-Spangled Banner” was loved by American composer and bandleader John Philip Sousa. He considered it a “soul-stirring song,” and once offered following about it: “Nations will seldom obtain good national anthems by offering prizes for them,” he said. “The man and the occasion must meet.”

And if Key got anything right, it was being at the right place, at the absolute most perfect of moments. Which ain’t a bad place to be, for most any lawyer, still...

Comments

Post a Comment